Introduction

Idealism and Christian Theology: Idealism and Christianity: Volume 1 (ICT from now on), by Joshua R. Farris (Editor), S. Mark Hamilton (Editor), and James S. Spiegel (General Editor) is a well-constructed collection of articles aimed at showing the relevance and plausibility of theistic idealism as set forth in the works of Anglican bishop and philosopher George Berkeley (1685-1753) and New England preacher, theologian, and philosopher Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). The articles not only expound on the respective ontologies of those two thinkers, but they are also constructive in that they aim (in different ways and degrees) at producing developments and offering possible corrections. I need to start by saying that "idealism" is notoriously difficult to define. In addition to that, and in relation to the volume reviewed here, Edwards' and Berkeley's respective idealisms have both similarities and differences (see chapter 2). Nevertheless, it seems safe to say that theistic idealism (both Berkeley's and Edwards') includes at least the following principles.

1. Nonmental entities are mind dependent. In Berkeley’s famous formulation, “Their esse is percipi.”

2. The only things that exist are minds and their contents; nonmental entities are thus not really nonmental at all, but are the contents of minds. “. . . there is not any other substance than spirit, or that which perceives . . . that therefore wherein colour, figure, and the like qualities exist, must perceive them.”

3. Physical bodies consist solely of our perceptions of them. “. . . what are the forementioned objects but the things we perceive by sense, and what do we perceive besides our own ideas or sensations . . .?”

4. God is the immediate cause of our perceptions of physical bodies. “. . . nothing can be more evident . . . than the existence of God, or a spirit who is intimately present to our minds, producing in them all that variety of ideas or sensations, which continually affect us.” (p. 198, from James M. Arcadi's article)

Nevertheless, there is more to Edwards' and Berkeley's, and I hope that what idealism is in this context will become clear as I go through the articles which compose this volume.

The contents

The "Introduction" is a presentation of the scope and relevance of the book as it aims to retrieve "ideas and arguments from its most significant modern exponents, especially George Berkeley and Jonathan Edwards, in order to assess its value for present and future theological consideration. As a piece of constructive theology itself (i.e., an approach to both systematic and philosophical theology, which draws from analytic resources for the purpose of clarifying, analyzing, developing, and extending theology as it is situated in particular traditions), this volume considers the explanatory power an idealist ontology has for a variety of issues in contemporary Christian theology" (1). I like the following: "Investigation into ontology is necessary for the task of Christian theology" (2).

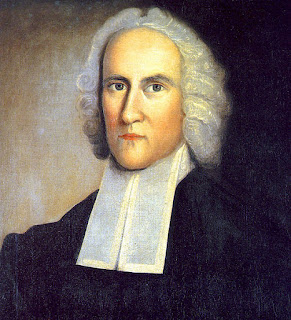

In chapter 1, "The Theological Orthodoxy of Berkeley’s Immaterialism," James S. Spiegel aims at showing how Berkeley's "metaphysics acknowledges and exploits this biblical convention" and "that Berkeleyan immaterialism enjoys at least as much and perhaps more explanatory power than matterism when approaching key biblical passages such as the Genesis account of creation" (27). I found it very interesting how Spiegel helpfully explains how idealism faces no more difficulties than matterism regarding the problem of moral evil (independently of Berkeley's own theological orthodoxy, which arguably seems sound anyway).

|

| George Berkeley (1685-1753). |

With regard to immoral actions performed by human beings he notes first that “the imputation of guilt is the same, whether a person commits such an action with or without an instrument,” where in this context the “instrument” on the matterist’s account is understood to be material substance. In this way, Berkeley argues that his immaterialism is, for good or ill, on equal footing with realism when it comes to the problem of moral evil. If given his principles, the benevolence of God must be denied because of the presence of moral evil in the world, then the same follows for the philosopher who assumes the principles of matterism. Interposing material substance between God and human misconduct provides no buffer against divine responsibility. Just as a murderer is equally culpable for his act whether he uses a gun or his fist, God is culpable (if culpable at all) for natural evil whether or not he created the world using corporeal substance. Thus, Berkeley’s intention here is simply to show that any theodicy that works here for the matterist works equally well for the immaterialist. There is no difference between them on this issue ... It is not immaterialism specifically that is indicted here but the more general doctrine of the immediate providence of God. Berkeley’s principles place him squarely within a much larger tradition of Christian theology that affirms the divine foreordination of all things. Anyone within this tradition, including those of the matterist stripe, must grapple with the thorny problem of reconciling divine determinism, human responsibility, and the goodness of God ... Berkeley’s immaterialist metaphysics does not subject him to any more formidable problem of evil than that which confronts certain other matterists. For both the task of forging a satisfactory theodicy in light of the sovereignty of God is equally onerous. (15-16)

In chapter 2, William J. Wainwright's "Berkeley, Edwards, Idealism and the Knowledge of God," the author offers a very helpful comparison between Berkeley's and Edwards' idealism, expounding both the similarities and the differences. The article also helps getting rid of some misconceptions, for example, by noticing how "Berkeley takes for granted the truth of the common sense view that objects continue to exist when no finite minds perceive them" (37ff). Wainwright concludes by stating that "One of the principal aims of Edward’s published and unpublished work, then, was, like Berkeley’s, to defend revealed religion in general, and Christianity in particular, from the attacks of its freethinking critics" (48).

Chapter 3 is titled "Idealistic Panentheism: Reflections on Jonathan Edwards’s Account of the God-World Relation." In it, Jordan Wessling argues that Edwards holds to a variant of panentheism (emphatically not to be confused with pantheism) in virtue of his view according to which created minds are, not independent substances, but ideas of God's mind radically God-dependent. In spite of this unusual variation, however, Wessling argues that Edwards successfully maintains a proper doctrine of the distinction and relation between God and creation.

Edwards’s idealistic panentheism has a unique and perhaps fruitful way of conceptualizing both God’s transcendence and his immanence. As the necessarily existent, sole substance in the world (and given Edwards’s ocassionalism, the sole cause as well), God is radically different from all of the “shadowy,” non-substantial creation. Yet, since the world exists within the mind of God, there is no corner of creation where he is not. The very substance or being of God is omnipresent as it is the divine mind/substance that “upholds” and “stands beneath” all of (ideal) creation. (59)

In a similar positive light, the article sees Edwards' "direct account" of God's conservation of creation.

For God to conserve creation is to simply think about it in the manner necessary for the relevant collection of ideas to count as creation. I add qualification “in the manner necessary for the relevant collection of ideas to count as creation” because presumably not each collection of divine ideas raises to the level of creation. However, it seems to be a plausible assumption that there could be something other than material creation that appropriately designates one collection of divine ideas as creation. If so, then for each moment that creation exists, it exists if and only if God thinks about creation in a relevant way. (60)

The author also believes that Edwards' idealistic panentheism also helps with the requirement of parsimony in ontology.

Idealistic panentheism is every bit a philosophical framework as much as it is a theological one. Idealistic panentheism is in fact a kind of global or all-encompassing ontology, and as such, assessments along these lines are paramount. It seems, furthermore, that idealistic panentheism succeeds on at least one influential criterion for the success of a global ontology, namely parsimony. For on idealistic panentheism only God and his ideas exist. Thus there are no dualisms of kinds of substances (as we have seen with Edwards, God is the only one true substance) and hence there are no interaction problems between radically different kinds of entities (e.g., spirit and matter). Nor can the idealistic panentheist be accused of multiplying entities without warrant. (58)

I have a few disagreements. First, Wessling portraits Edwards' (soft) determinism (or compatibilism, if you will) as a problem.

Ideas are the kinds of things that are ultimately determined by external causes. In the human case, ideas are often determined by such influences as the will of the thinker, other mental states, biochemical operations, psychological history, and environmental inputs. But with a sovereign and omnipotent God, it seems that God’s ideas (when considered as a complete set) must be solely governed by the nature of God (including the nature of the divine mind) and his will. After all, it does not seem right that God’s ideas would, so to speak, “have minds of their own” that can exercise independent, contra-causal libertarian freedom. And it seems downright impious to suggest that God’s ideas are governed by genuinely random processes. Finally, if idealistic panentheism is true, there is nothing outside of God’s mind that can influence the shape of God’s ideas. But given all of these conditions, it seems that it must be God who ultimately determines his ideas, by choice or by his nature or some combination thereof. In which case, determinism is true—since the world just is a collection of divine ideas that is ultimately determined by the will and nature of God. It is no wonder that Edwards was such an ardent defender of theological determinism! (61-62)

No wonder, indeed, in the light of Edwards' Freedom of the Will! But what is unattractive to some is attractive to others, and I belong to the latter group.

Also, in the context of the problem of evil, Wessling talks of creation as "part of God" (63-64). No textual reference or proof is given for such a claim, which, in fact, I believe is ungrounded. For Edwards, creation is God's collection of ideas, but that does not necessarily entail that those ideas are "parts" of God's being (which would contradict a host of passages where Edwards asserts divine simplicity and aseity). No doubt Edwards' view raises the question of how to think about those divine ideas and their relationship with God, but making those ideas "parts" of God's own being is not entailed by Edwards' ontology (I made a similar point in my review of John Bombaro's Jonathan Edwards' Vision of Reality, section "A disagreement"). That said, the article is helpful and fair both towards Edwards and his sympathizers (Wessling himself offers some possible solutions to the possible difficulties faced by Edwards' idealistic panentheism).

Chapter 4 contains Keith E. Yandell's "Berkeley, Realism, Idealism, and Creation." In this brief ("the price of brevity in the face of interpretative fecundity," 73) but helpful article, the author offers ontological and epistemological considerations aimed at showing Berkeley's idealism as a possible option for explaining the relationship between God and creation. In addition to some noteworthy critical remarks on Berkeley's imagist theory of meaning (and in spite of a bizarre claim about the B-theory of time), the paper helps to clarify what is the realism that Berkeley rejects (and, consequently, what is the realism the he embraces).

In chapter 5, we find "Edwardsian Idealism, Imago Dei, and Contemporary Theology" by Joshua R. Farris. This article was a pleasant confirmation since Joshua and I reached independently some of the same conclusions on those issues (although, I admit, I should have been aware of his article before writing mine). The paper discusses Edwards' doctrine of the relationship between body and soul, and it offers some constructive Edwardsean ways to think about the imago dei aided by the doctrine of God's nature and action. Contrary to some critics, and similarly to Wesseling, Farris argues that

Edwards can affirm what some have construed, in the contemporary literature, as the traditional and orthodox view of the Creator-creature relation in that Edwards can affirm God’s transcendence from creation, but also the intimacy and immanence of his nature to human creatures without assuming the supposed “modern” divide between the two notions. In this way, then, God is said to encompass all of reality, most importantly human reality—as the one above and as the one present to it. (95)

It's a fine article, and I found it helpful for understanding even further Edwards' distinction between the natural and the supernatural/moral image of God in man. However, like for chapter 3, I have doubts about the extent of Edwards' view of divine ideas and theosis is portrayed (93, 97-98, 101).

Chapter 6 contains another good article, "On the Corruption of the Body: A Theological Argument for Metaphysical Idealism," by S. Mark Hamilton. Aptly placed after Farris' article as they have some topics in common, Hamilton discusses ways to think about the corruption of the body, as a consequence of the fall of mankind into sin, within the framework of Edwards' metaphysical idealism. I found it helpful in order to better realize "the difference between what the mind-body dualist calls a material body and what the idealist refers to as a physical body" (117). At page 118, I found a similar unreferenced claim present in chapters 3 and 5.

Marc Cortez discusses "Idealism and the Resurrection" in chapter 7. The article offers a few key but sometimes neglected points in order to understand Edwards' metaphysics, such as, for instance, the following one about perception.

Edwards also rejects the notion that material objects are mind-independent realities, contending instead that these property-bundles can only exist insofar as they are perceived by some conscious being. In Edwards’s view, when I say that an apple is red, what I really mean is that God is currently producing all the properties of appleness (solidity, shape, taste, etc.), along with the corresponding property of redness. But what could it mean to say that God is producing these properties unless we mean that he is causing some conscious being to experience the requisite properties? After all, he cannot mean that God is causing the properties to adhere in some substance, since there is no such material substance. Thus, he must be acting in such a way that the properties really “adhere” in the conscious experience of some perceiver. This is what Edwards means when he concludes that “nothing has any existence anywhere else but in consciousness” and that “the material universe exists only in the mind.” For Edwards, then, a material body is much more of an “act” or “event” than it is a “thing” or “substance.”

However, this does not mean that created things do not exist in a meaningful sense of the word.

This does not mean, however, that material bodies lack any meaningful existence. Although material things do not exist “on their own,” they have a stable mode of existence in God’s constant and consistent activity ... The existence of material objects is grounded both in God’s “stable idea” of those objects and in his “stable will” by which he consistently and perfectly communicates that idea “to other minds.” In that restricted sense, Edwards can even refer to material objects as having “substance.” [Continuing in endnote 16: In this more limited sense, then, “substance” refers to an object that has this kind of “stable” existence and that consequently impacts how we experience the world. Thus Edwards contends that such objects continue to exist (in at least some sense) even when they are not being directly perceived by any conscious mind because God continues to constitute the perceptual experience of created beings on the basis of the supposition of such material objects.] (131-132, 140)

Cortez then continues by discussing the coherence of the resurrection of the body, together with the intermediate state, in Edwards' thought. Cortez sees a significant problem with Edwards' very positive description of the intermediate state. However, he seems to make the problem slightly bigger than it is when he claims that both Edwards' "lofty descriptions of the intermediate state and his speculations on the possibility of immediate spiritual knowledge point toward a view of humanity where the body appears somewhat extraneous" (138), especially when considering that Cortez himself (assuming the problem) suggests that possible modification can be made without significant modifications to Edwards' thought.

Chapter 8 contains Oliver D. Crisp's "Jonathan Edwards, Idealism, and Christology." According to the author, the paper's argument "has two parts. The first offers an overview of the aspects of Edwards’s metaphysics relevant to his Christology, focusing on his immaterialism, metaphysical antirealism, occasionalism, and pure act panentheism. The second sets out the Christological implications for these four doctrines, including the theological obstacles they present for the orthodoxy of Edwardsianism. In conclusion, Crisp offers some reflections on the implications of Edwards’s idealism for his Christology" (146). It is a lengthy paper that provides a handy critical summary of Edwards' view on the issues in question.

"Jonathan Edwards’s Dynamic Idealism and Cosmic Christology" is Seng-Kong Tan's paper that we find in chapter 9, perhaps my favorite paper in this collection.

In this essay, I utilize Edwards’s Trinitarian musings, particularly on the reciprocity of Word and Spirit, to illuminate and exegete his philosophical idealism in two parts. First, I argue that Edwards’s pneumatic idealism is grounded in the divine being and is crucial to his construal of the created order. Not only do I show that pneumatic action ensures the dynamism and objectivity of this ideal, physical universe, in part two, I argue that this very same Spirit causes the being and identity of the incarnate Logos. (178)

I believe Tan meets his goals. The paper is pleasantly theological, but it also contains important philosophical discussions and clarifications such as the following.

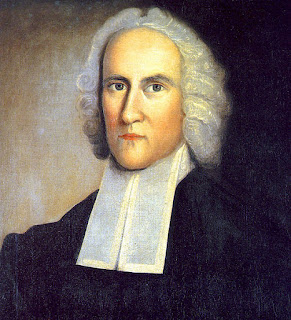

|

| Jonathan Edwards (1703-1758). |

For Edwards, his idealism is not meant to displace the commonsense, scientific conception of the universe: "Though we suppose that the existence of the whole material universe is absolutely dependent on idea, yet we may speak in the old way, and as properly and truly as ever." For, "all the natural changes in the universe . . . in a continued series" are commensurate with that completed, virtual series of ideas in the Logos." That is why "divine constitution is the thing which makes truth:" for it includes both an ontic and epistemological correspondence between the actual to the virtual ideas in God. That individual identity of a created thing is not located in itself, be it in an underlying substance or otherwise, need not undermine creaturely integrity For a created thing to be dynamically recreated and reconstituted as singular testifies to its utter poverty of independent being and its radically dependent ontological relation to God. This oneness of the physical universe is, therefore, not an illusion to God or human beings." (184)

Tan's article reminded me of his excellent Fullness Received and Returned: Trinity and Participation in Jonathan Edwards.

Chapter 10 offers James M Arcadi's "Idealism and Participating in the Body of Christ." Assuming Berkeley's idealism, the article's goal is to argue that the model of the Eucharist (which he calls "impanation") the author offers "makes best sense of the conjunction of the commitments to idealism and the corporeal presence of Christ in the Eucharist" (198).

Any Christian theologian faced with the task of interpreting Christ’s utterances at the Last Supper is in for a challenging project. Those sympathetic to idealism and to a corporeal presence interpretation of these utterances are in for an even stiffer challenge. For how could Christ be said to be bodily present in the Eucharist when none of the sensible qualities of his body are presented to the minds of the recipients? This trouble is compounded in corporeal presence theories of the Eucharist that explicitly state that the sensible qualities of Christ’s body are not present in the Eucharist. On an idealistic metaphysical framework, this surely entails that Christ is not bodily present in the Eucharist. Faced with this dilemma, one might be tempted to give up idealism or give up on corporeal presence notions of Christ in the Eucharist. However, I have argued that impanation, and specifically Type-S Impanation, is able to deliver on the corporeal presence of Christ in the Eucharist within an idealist ontology. (210)

The argument in and of itself seems formally valid, and it is very interesting to follow its course assuming (for the sake of argument) one of the two premises, i.e., a doctrine of the corporeal presence of Christ in the Supper (the other premise is idealism). However, since premises are the grounds upon which an argument stands or falls (including when the argument is formally impeccable), and assuming the dilemma is real, one could not feel any need to give up idealism because there is no need to accept a corporeal presence. Arcadi himself says: "If the model I offer is not accepted, I suggest one must give up one of these conjuncts" (198). Personally, I have still to meet a proper biblical and philosophical explanation of how Christ can be fully and truly human and be in any sense corporally or bodily present elsewhere than where his body is. Therefore, I find a corporeal presence dispensable.

Finally, we have chapter 11 with Timo Airaksinen's "Idealistic Ethics and Berkeley’s Good God." The author seeks to show what follows.

Berkeley’s idealistic ethics: one cannot define moral notions and conscience without a reference to the mind and its functions or, in this case, God’s will. He is the ideal model and the measure of the good and the right, or virtue. There are no other adequate models. In other words, it only makes sense to talk about ethics in a theological context. To talk about the good and the right as do the scientifically minded mechanist materialists and supporters of enlightened atheism— or the “free thinkers” of Berkeley’s time— is to miss the indispensable spiritual components of ethical terms. Hence, Berkeley is an ethical idealist in the Platonic sense: his faith in God allows him to define the ethical ideals, or the model principles of moral conduct and the measures of ethical life, in an idealistic fashion. His ethics rests on idealistic metaphysics— it is metaphysically informed as it tracks God. (218)

The paper helps the reader towards that stated direction. Nevertheless, the article leaves the impression to possess an expository and argumentative potential that was not actuated as it could have.

Concluding Remarks

One thing that this volume made me realize even more is that labels, although necessary, can be misleading at times. There are a lot of misconceptions regarding idealism, from simple misunderstandings to grandiose statements regarding idealism's allegedly inexorable slippery slope into full skepticism. I believe that part of the reason for these misconceptions can be partly summarised by using the words of German philosopher Kurt Flasch. Although what follows is related primarily to Medieval theologian and philosopher Meister Eckhart (1260–1328), it can apply to other "influential thinkers" such as Edwards.

"The works and ideas of influential thinkers, because of their rich complexity, seem different to every historical age; they oscillate, unconcerned with how we categorize them. But anyone who starts to work historically looks for order; he needs labels, and so he clings to disciplinary affiliations, intellectual currents, titles. Historical thinking thrives on rebelling against this initial manner of categorizing, classifying, and designating, especially in philosophy, where certain labels—like idealism, realism, and so forth—are almost never used without doing injustice. They drown the individual thinker in currents. Our task here is to try to grasp Eckhart's intellectual world, the private world of a misfit, through his writings; other labels we may bring to the text are dismissible and of no real value, except perhaps for their preparatory and didactic nature as aids to a first approach. Nothing can be inferred from them about Eckhart. At best, they are heuristic tools." ~ Kurt Flasch, Meister Eckhart: Philosopher of Christianity, 14.

In this regard, one of the main benefits I got from the reading of this book was further knowledge and clarity regarding 1) Berkeley's and Edwards respective idealism, and 2) terms (idealist, realist, matterist) and issue at stakes in these often complicated metaphysical debates, which in turn 3) help me to further clear my mind from perplexities and misconceptions regarding theistic idealism.

I also liked that the articles focused on Berkeley's and Edwards' idealism, which I think helped keeping the articles unified.

A book for the discerning reader, I recommend it to the student and to the scholar. It is not only a contribution to Christian theistic idealism, but also to Berkeleyian and Edwardsean studies.

Review copy kindly provided by Bloomsbury.

©