"I admire Tolkien greatly. His books had enormous influence on me. And the trope that he sort of established—the idea of the Dark Lord and his Evil Minions—in the hands of lesser writers over the years and decades has not served the genre well. It has been beaten to death. The battle of good and evil is a great subject for any book and certainly for a fantasy book, but I think ultimately the battle between good and evil is weighed within the individual human heart and not necessarily between an army of people dressed in white and an army of people dressed in black. When I look at the world, I see that most real living breathing human beings are grey." ~ George R. R. Martin (for Martin's more extended assertions, see here and here).

So, one of the things that Martin's words imply is that J.R.R. Tolkien is too dualistic: evil all on one side, and good all on the other side. Tolkien would be a sort of ethical dualist, or a Manichean or a Gnostic or some kind.

But then you think about Tolkien's saga, and you see that things are not as Martin puts them.

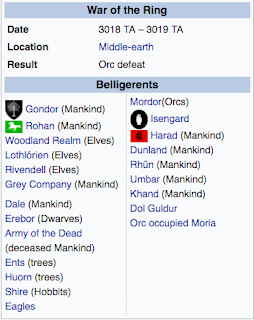

|

| Six nations of men join Sauron in the War of the Ring. And let's not forget Gríma Wormtongue. [Picture from Wikipedia, War of the Ring] |

- The seven kings of men give up and join Sauron quite soon, after receiving the rings

- The virtuous king Isildur refuses to destroy the Ring once on Mount Doom.

- The totally normal Hobbit Smeagle kills his best friend for the Ring.

- Saruman, sent on the earth to fight Sauron, joins Sauron.

- The hero of Minas Thirit, Boromir, almost steals the Ring from Frodo.

- Galadriel, the most powerful and good elf in the middle earth, is powerfully tempted by the ring.

- Countless men from the south and east join Sauron.

- Pirates (men) join Sauron.

- Gondor's ruling steward, Denethor, a person from a glorious family, willfully gives up to hopelessness and madness.

- The Battle of the Pelennor Fields is won ultimately because Aragorn cunningly enlists The Army of the Dead, a stinky group of once traitors and now undead and undying soldiers and scoundrels who mercenarily accept to fight for him merely because Aragorn, as Isildur's heir, promises to free them from their curse.

- At the end of his journey, the hero of the entire LOTR book, Frodo, gives up to the power of the Ring.

- Gandalf is sometimes quite rude.

The Men (as well as the elves, the Dwarves and the Hobbits) of Tolkien's world, including its heroes, are complicated beings who fight against inner temptations and against the evil of a dangerous and violent world. But maybe Martin has read a different Tolkien. 😊

Then, I do not think Martin's books (Games of Thrones, of which I have read the first two before giving up to boredom) see "humans as grey." I think his books reflect the fact that the author sees men as black as they can get. The best characters in his saga are despicable individuals. Sure, mankind is spiritually depraved in my view. I agree that "ultimately the battle between good and evil is weighed within the individual human heart," but I do not see any of this in Martin's GoT. Both in real history and in Tolkien's world there is also redemption and virtue. There is not a hint of such things in GoT. All is, not grey, but pitch black. In the universe of Martin's soap opera of murders, betrayals, and wars (with several sprinkles of sex and dragons to attract more people) there is no goal nor purpose but one: to repeat ad nauseam that human beings are dark creatures that live only for power (alternatively, pleasure) and survival, and that is the end of the story and the bottom truth of reality. Therefore, if Tolkien is a dualist (and he is not), Martin is certainly a hard monist. Martin seems to have a specific worldview at the bases of his GoT stories, and, even though I do not know what this worldview exactly is, it generally looks like a sort of hard monism with a monolithic view of man, history, and things in general. In this sense, I think Tolkien's writings are way more "realistic" (and exceedingly more edifying) than Martin's.